Against Enthusiasm

Modern life is one endless sugar rush. Only a healthy dose of cynicism can save us now.

They are everywhere one looks. The mandatory symbol of the overfamiliar: ‘We’ve got your order!’

To the grammatically sane, reading the exclamation mark in its proper mode, the modern world appears increasingly deranged, authored seemingly by caffeinated twelve-year-olds. The delirium jumps at you in emails, on billboards, from the end of every other sentence.

The exclamation mark—the name a dead giveaway—means to exclaim. To cry out or speak suddenly or excitedly, as from surprise, delight, horror, etc. That line and dot seize your attention. Help! Now, it seizes your last nerve. Stop! If everything is exclamatory, then nothing is.

To the cynic, the exclamation mark is a hypodermic needle spiking foreign joy into the bloodstream of language. With each excitable email, I wonder, is this person in need of urgent medical attention? Or have they overdosed on Adderall?

Perhaps I’m not of a sunny disposition. Ancient therapy notes confirm my suspicions. Mercifully, the provenance is biological, not environmental.

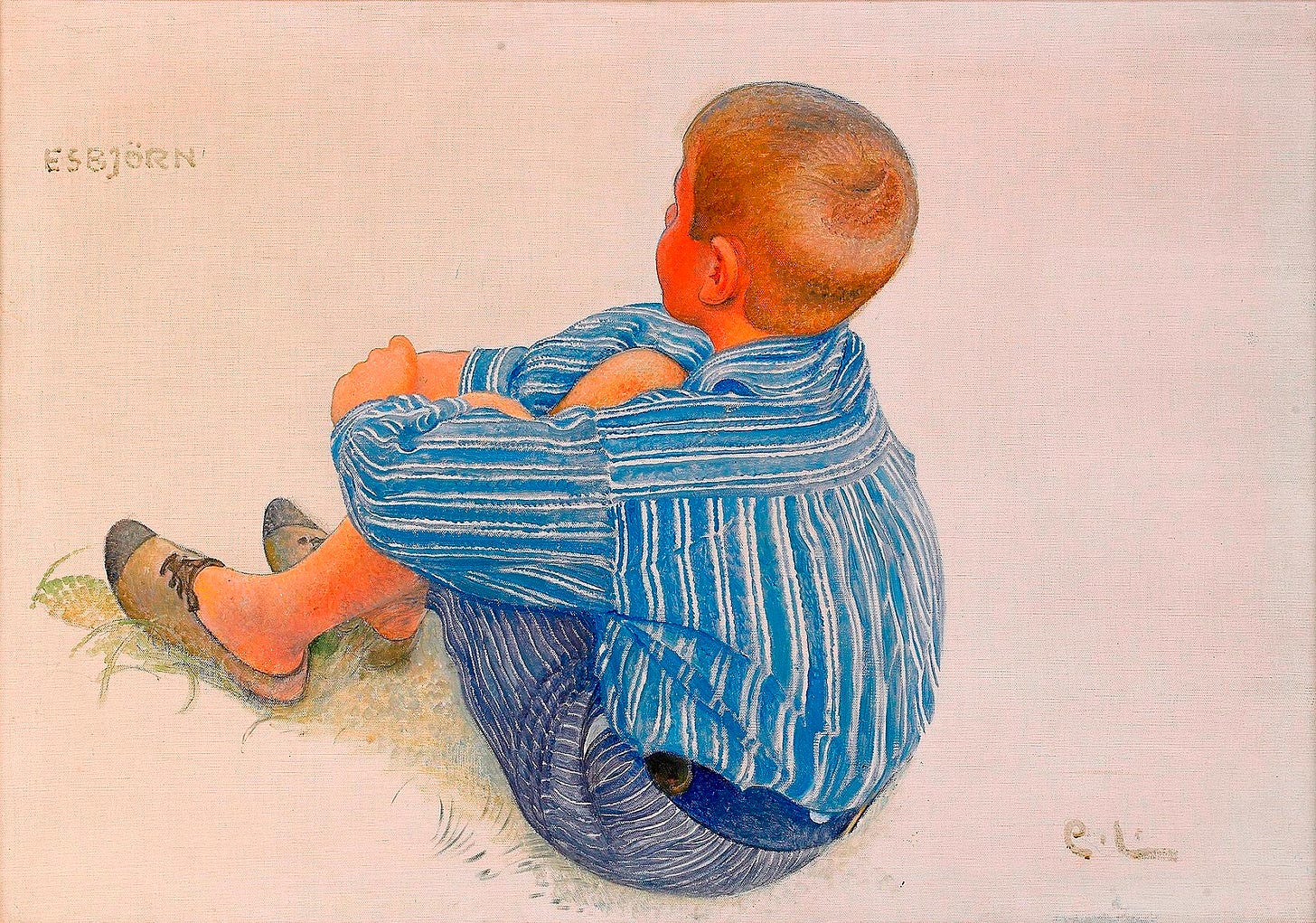

The five-year-old edition of me was unimpressed with the world around him. Doctor Richardson, a child psychologist and family friend, was equally unsparing:

“Obsessive-compulsive. Makes sardonic remarks. Cynical.” I was supremely fortunate, I think. A happy childhood inadequately prepares you for real life.

It’s been a minute. Nothing, aside from growing both upwards and outwards, has changed. Today, we’d suspect Dr Richardson’s workmanlike prose to lack enthusiasm. He observed. He reported. He reported what he had observed.

This is of course the age of positivity. Optimists call it the age of self-awareness. Cynics call it the age of self-obsession. One of us is wrong. And it isn’t the cynic. A cursory glance over human history suggests that life isn’t all matcha and mindfulness. To articulate such findings reveals oneself a cynic or worse—a misanthrope.

The cynic provokes militant inquisition from the sunny, the optimistic, the hopeful, the credulous, the gullible—the delusional. Have you ever heard a fellow human being describe themselves as ‘happy-go-lucky’? What image springs to mind? A golden retriever dutifully chasing its tail.

In the cynic’s dictionary, happy is a euphemism for stupid. Lucky a synonym for incurious. Happiness—that lobotomic ambition—enchants children, and the improperly medicated.

At least, it appears that way. Donate a few minutes of your life and a few strips of grey matter: browse LinkedIn. Shiny buttons offer a gamut of preset replies:

Great job! Insightful! Congratulations!

Don’t overstay your welcome. You may slip into a diabetic coma.

What is a cynic? The cynic sees things as they are, and not as he’d like them to be. To the mindful majority, polluted with syrupy affirmations and good vibes, reality is optional—pervious to their wellness sermons.

Interrogations spill from their rictus grins. The optimist joshes confidingly: You’re just saying that! Next comes exasperation: C’mon! Their faces crash like a fat man through a trapdoor. Oh, you’re just a contrarian. Gone is the scarlet letter of the optimist—the exclamation mark.

Contrarian is the c-word beloved of c-words. No c-word offends the cynic quite like contrarian. To brand a cynic as a contrarian is to set his teeth into you. The very word suggests an intellectual crossdresser flashing from the bushes.

Its announcement is a capital offence. After all, the accuser wielding the c-word is the guilty party. To cling to a sunny disposition post-reading age demands titanic reserves of self-deception. Whatever or whomever dumped us onto this planet was clearly not an optimist. See: Civilisation, History of.

The cynic cheerfully absorbs name-calling, both vagrant and opaque. We’re not pessimists. We don’t expect the worst. We’re not nihilists either. Cynics are to nihilists what celibates are to eunuchs.

Jonathan Swift endured the label routinely stamped on the unrepentant cynic—misanthrope. Cynics—true cynics—are none of these things. Cynics believe things would get better if only we stopped lying about how awful they can be and currently are.

Much like the maligned Dean Swift, cynics are often enraged idealists. Swift confessed he “hated and detested that animal called man.” He was serious. Swift loved humanity too much to play pretend.

One term I happily claim is curmudgeon. The Portable Curmudgeon, a timeless portal of good sense, offers the definition:

1. archaic: a crusty, ill-tempered, churlish old man.

2. modern: anyone who hates hypocrisy and pretence and has the temerity to say so; anyone with the habit of pointing out unpleasant facts in an engaging and humorous manner.

Let’s assume the modern definition. The curmudgeon, after all, accepts the one eternal truth: if you wish to tell someone the truth, you’d better make them laugh.

The cynics of ancient Greece knew that. Diogenes, the father eternal of philosophical cynicism, traipsed the daylight streets of Athens clutching a lamp.

When questioned, he replied: “I’m looking for an honest man.” He went to the grave having never found one.

The ancient cynics believed that a good life of virtue and contentment demanded clear eyes and an honest tongue. The cynics rejected the ancient lusts for power, wealth, status, and glory.

But the modern cynic is nothing if not realistic. The world—what’s left of it—needs more cynics and fewer HR-approved wellness retreats. We need the man willing to say stop! Exclamation mark and all. The modern cynic rejects the next big thing, resists the fashionable, sniffs at the reheated claims of sentimentalists and Utopians. They know how such fever dreams often end: with empty barrels of Flavour-Aid and a carpet of twitching cadavers.

But that doesn’t mean the modern cynic is negative or a misery. He or she is merely an idealist armed with data. He’s the man who refuses to applaud mediocrity or the woman who forgoes the social tax of false flattery.

The modern cynic asks why we allow the Silicon Valley set—zealots convinced the human condition is just faulty software—to uproot everything we know and hold dear in their ludicrous game of Progress.

If the optimist is the accelerator pedal, then the cynic is the brake which stops the bus from barrelling over the edge and exploding on the jagged rocks below.

And if he refuses the exclamation mark, it is for vital reasons. The modern cynic prefers the full stop. After all, progress—true and worthy progress—requires plenty of time to stop and think.

I have always been called a cynic, though I prefer realist. My wife calls me a curmudgeon, though she means the archaic definition.

As you point out, the cynic/realist is not a pessimist; if the optimist sees the glass half full and the pessimist sees it as half empty, the cynic remarks, "It depends on whether you're drinking or pouring."

I definitely resist doing anything that might be considered trendy. I tell everybody that I'm expressing my individuality by not having a tattoo since everyone and his mother seems to have several now.